I awoke hours before the alarm clock went off. I curled on my side like the swirl of a shell, hollowed and echoing emptiness within. My hand rested on my belly, swollen beside me.

I showered that morning, letting the hot water run down my face, mingling with tears. My eyes were puffy, the whites traversed with spidery red lines like an atlas of the world. They stared back at me from the swiped clearing I made through the thick steam on the mirror. I was a lost girl. My ragged wet hair dripped onto my bare shoulders like I was being pulled down and drowned by the weight of my pain.

We drove to the hospital in silence. There weren’t any words worth saying.

The doctor would explain everything again while Josh held my hand, churning it in his as if wearing smooth a prayer bead.

I’d sign papers and undress. I’d put on a hospital gown and remove my wedding ring, handing it to Josh along with my things. He helped me climb awkwardly into the bed with the railings locking into place like a trap. And I’d lay my arms open offering my veins for the start of an IV. I’d count the tiles in the ceiling as they wheeled me under the florescent lights, clearing my mind out by filling it with nothing.

There would be a rush of people in and out, a swish of hospital scrubs and stethoscopes and the ragged rip of the blood pressure cuff tearing apart to be strapped over my arm as the pressure increased and the thud of my heart pumped in my ears.

It amazed me that my heart could just keep pumping when it was so broken.

The week before we sat anticipating another heartbeat. But the thud was missing when my doctor rubbed warm jelly onto the ultrasound wand and waved it over my belly. Like a magician saying abracadabra, the screen came to life, a whoosh of static and a faint immovable outline. His hand slowed. He’d furrowed his brow then and called me kiddo as he explained how things had gone so wrong. How there should be movement and a fetal heartbeat, how the silhouette of my baby was not a magic trick, it was a disappearing act. An apparition, a loss, how the flutters I felt were never going to get stronger.

I would be asked the same questions over and over as the shifts changed and my bed was wheeled into the pre-op and post-op. They’d ask me to state my name and birthday and what I was being treated for as they checked my chart and lifted my limp arm to match it to my plastic armband.

My voice was even, a monotone recitation. I was there for a D & C. I would tell them 16 weeks. I would tell them Alia, and 22 years old. And then I would add miscarriage just in case. So they would know that the baby they were about to take from me was already gone. My body just hadn’t caught up yet.

I would wake groggy, my throat sore and raspy, my IV tubing falling across my face as I wiped at my eyes, waking to a new reality. And later, when I was discharged, I would pull on my stretchy pants, belly still swollen but hollow all the same, and shuffle out of the hospital.

I wouldn’t ask questions like why?

I’d seen others live a life devoted to their grief. But I feared that relenting to the pain and asking hard questions belied a small faith, not enough trust in the sovereignty of God, and too much focus on the here and now. I believed eternity is what mattered and getting there had less to do with flourishing here as it did a blind devotion to the right answers.

I worried God might not have the answers to the questions I had, so I summed up life in Bible verses, in parables and tidy lessons without looking too hard for the meanings of things. I wanted a shortcut to bypass the pain. An antidote to suffering.

I wasn’t sure my God could stand up to the scrutiny if I let loose all my doubts.

So I learned to fear the unknowns, the emptiness, the messiness of life and indeed death. I feared faith. I wanted certainty and promises I could control. I wanted a God I could contain within the highlighted portions of my study Bible, not One who met me in operating rooms filled with loss.

But grief pushed down comes out sideways.

It’s taken me years to learn to grieve lost things.

I wish I had know this life will ache with emptiness and it’s ok not to rush to fill it. It’s ok to leave some questions on the books. It’s ok to be angry and to admit we can’t see the good of it all right now. To sit on the floor in my baby’s room and weep over the blankets and the onesies and the carseat we hung on to that would be packed up.

I wish someone had told me it was ok to relent to sadness, to doubt, to loss. I wish someone had told me it was ok to succumb to anger, to the great and formidable why? I wish I had understood that God is undaunted by my humanity.

I wish I had understood that answers are not the reason we ask the questions. Sometimes we ask the questions to say, Who are You really, God? Who are You to me right now in this pain? The questions are the place to admit our need, not just for answers, but for awareness of who God is.

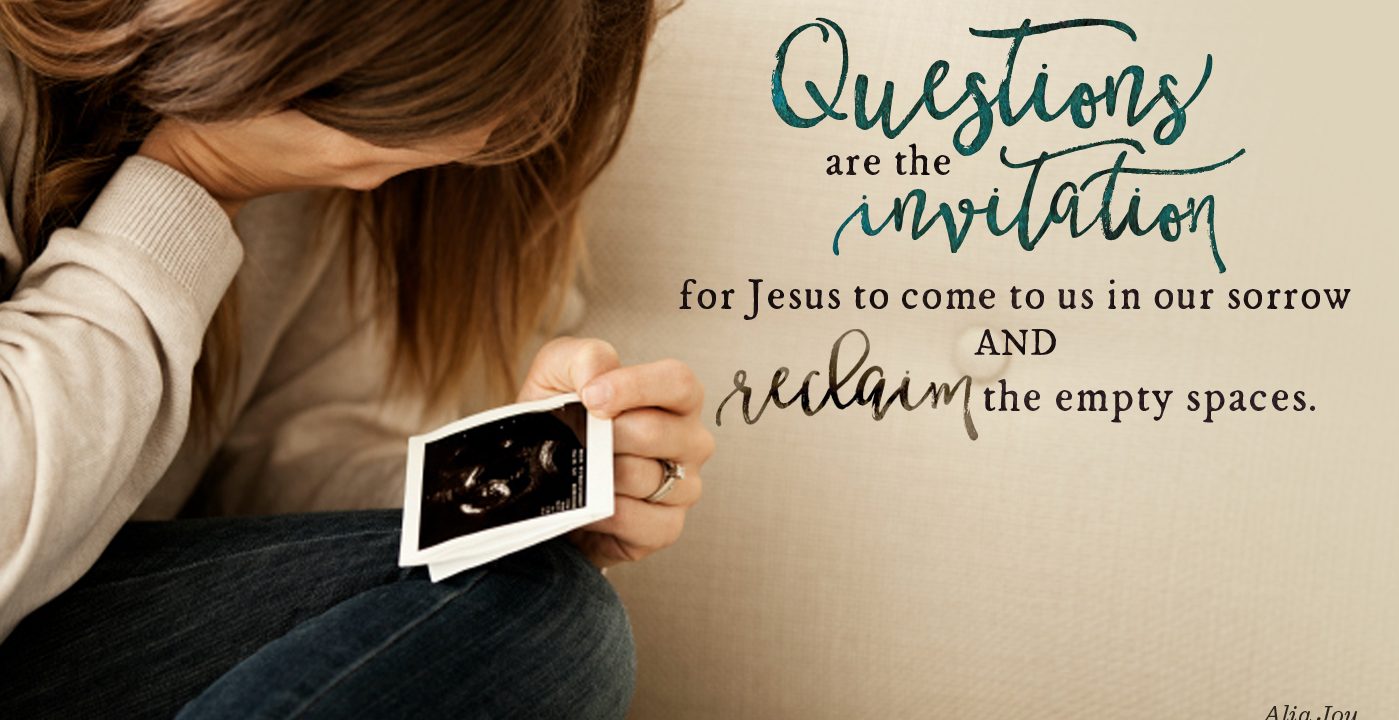

I wish I had known the questions are the invitation for Jesus to come to us in our sorrow and reclaim the empty spaces.

I wish I had known Jesus is the God of lost things.

[linebreak]

WOW! I really needed this today. So much truth for the pain I crawl through right now, having just lost my sister to the worst of tragedies. Thank you for sharing and so beautifully articulating so many hard truths. This touched me very deeply.

I hear your sadness over your sister’s death. Losing a sibling is hard, very hard. Alia is right – grieving the loss, sitting in your questions…just everything she said here is good. I was able to go to counseling with a Godly counselor who helped guide me through “complicated grief,” as they called it. Praying for peace and comfort for you and the sitting in the grief and loss and questions.

I am so sorry for your loss. It blesses me deeply that you found some comfort in this. Yes it is a hard truth but we have such hope as believers. It’s ok not to be there yet. It’s ok to not even know exactly where you are as you mourn. It’s ok to journey through grief and sit with the questions. I pray you feel Jesus near as you walk this road of grief and suffering and that you feel sheltered under the hand of the Almighty.

MaryGW,

Prayers for you as you grieve the tragic loss of your sister. May God guide your steps and give you peace and contentment. May you feel God’s loving arms surround you always!

(((((Hugs)))))

Thank you for sharing this today. I sent it to my friend who suffered a miscarriage several years ago who I know is still struggling with the loss, a struggle that has unfortunately also impacted her marriage. It is hard sometimes to see why we have to go through the trials that are given to us. Best wishes to you!

I could write so many more chapters about how our marriage fell apart after this loss. How God redeemed it and brought us back from the brink of an affair and a road headed toward divorce. Grief isn’t easy to navigate. It’s not something we’re taught to do well. It’s something we tend to sink in or skip over. I pray your friend finds comfort and that God brings healing to the broken places both in her heart and in her marriage. Thank you for being a good friend to her in the midst of it all.

Alia, I lost two babies, and years later my husband had an affair. I wanted everyone to be proud of how strong i was. I pushed my grief, my questions way down deep, all the time separating myself from the God I didn’t think I could trust anymore. Thank you for your words. Even after all these years, they brought healing.

Thank-you, too, for this piece. I experienced a miscarriage 17 years ago and the pain of grieving the loss of a little one has become this beautiful ache in my heart. It’s beautiful because God used it to birth an amazing work in my heart and it’s an ache because…well…just because. Thank-you for walking us through your grief.

God is good and merciful to us. We just can’t always see it this side of eternity. Still, I am glad you’ve found a place to comfort others as you’ve been comforted. This happened almost 14 years ago and I can still write about it like it just happened. You don’t ever really forget loss it just takes on different shapes as the years go on. There’ll always be an ache for the lost things this side of eternity. We’re not home yet.

THIS WAS MY FAVORITE LINE: I believed eternity is what mattered and getting there had less to do with flourishing here as it did a blind devotion to the right answers.

I can’t tell you how much time I have lost worrying about “flourishing” here in this world rather than living with blind devotion that God is in control, he can handle all my doubt and pain, and it is He I must run too. I can grieve and shine to others, all in His name.

Thank you for sharing, you really touched my heart. I am so sorry for your loss. May God bless you and your husband and may you see God shining through in every situation even the darkest ones. Xoxoxoxo

Thank you so much Stephanie. This was almost 14 years ago. God brought us through it and through another miscarriage after this one. I’m revisiting some of those broken spaces because I know so many women dealing with loss and questions and these are the things I wish I had known when I was in the middle of it. These are things I still need to remember when there’s pain I cannot understand.

Yes, yes, Alia. It’s all ok.

And this –>’It amazed me that my heart could just keep pumping when it was so broken.’

Somehow we continue on. That must be grace.

Always grace. Unceasing.

“I wish I had known the questions are the invitation for Jesus to come to us in our sorrow and reclaim the empty spaces.” Alia, God meets us in these empty spaces to show us His grace & mercy. At our lowest, He comes in to help us bear & come through difficult times.

This is one of the most powerful essays I’ve read on incourage. I wept the entire time. My grief isn’t the same, but my grief going sideways is the same. I didn’t quit believing in or loving God…I just kept the grief separate and hidden. Thank you so much for speaking your truth so beautifully. Right to my heart.

Sometimes it’s easier to compartmentalize parts of our lives away from God. There are the tender and bruised areas we don’t want touched, even lovingly. But I am so glad this spoke to your heart. Grief gone sideways always comes out in unpleasant ways. We have to dig into it to get through it.

Alia, this is all so very true, so very good. I have experienced the same journey with different losses and oh the difference it made when I learned too God is good with all our questions. Yes, grief comes out sideways when we think we are keeping it tucked away, because we are afraid to question.

I was a little girl when I lost my first two siblings and grief often gets put away when you are a kid. – when I lost my 3rd one (and only) the questions were too big to ignore, the grief too great and consuming. I will be sharing this. I think it is one of the best pieces on grief I have read for quite awhile.

Oh friend!! That is so much grief to bear. I am thankful we do not bear it alone and I’m thankful you found a place to work through it with a counselor and to arrive at a place where your own wisdom and experience ministers to others. It is a gift no one would ask to receive but God makes all things new. Sometimes here on earth and sometimes not yet. But we are being renewed day by day, it just doesn’t always feel like it.

“This life will ache with emptiness and it’s okay not to rush to fill it.” Alia, thank you for these raw honest words and for sharing this painful time in your life. It’s a comfort to me and a much needed reminder right now to be honest with God during the aching emptiness in my life.

It’s odd that being honest with ourselves and God is often the most difficult thing to do. Especially since God knows every inch of our hearts. What a beautiful reminder we have that God knows our every need even before we ever do.

Alia, I praise the Lord for your courage and care in sharing these tender and vulnerable words, experiences in this place. I am so sorry for your loss; my heart hurts at your loss. How many times do we hold back the gut-wrenching questions out of fear of offending the Lord or anger towards Him, of inserting a doubt into the holes that need to be filled by God. “I wish I had understood that God is undaunted by my humanity.”-powerful those words. I’ve had to learn that grief takes time and facing into the questions and pain with Him, moving through these moments that beg a drawing close to Him, to experience His grace and love instead of stuffing the pain back into the holes to “be strong.” Oh Alia, may we each find Him who is our peace and comfort today in these places, facing the pain pouring out into His strong shoulders, each tear that we shed with His caught in His bottle.

Yes, I’ve written before about how God wants our surrender more than our strength. We often mix that up and find it puts up barriers in our hearts to healing and wholeness. We try to patch it up ourselves instead of coming weary and empty and broken and even lost to the God who gets it.

Thank you.

I just lost my twins at 12 weeks. From a horrible situation that left me with so many unanswerable and aching questions.

Thank you for sharing this.

You will never know what this has meant to me.

I read this comment a few hours ago and just now had time to respond. This comment from you, dear one, brought me to tears. I am so very sorry for your tremendous loss. I have sent prayers to heaven today for you. I am so sorry for the ache and the unanswerable things. I’ve prayed for Jesus to be so near to you as you grieve and for you to know He can handle everything you’re feeling, the ugly and devastating and angry and doubtful. He is big enough and wants us to draw near with our whole broken self. He is a safe space to run to.

Thank you for your vulnerability and openness. I share almost the exact journey…I was 16 weeks pregnant, had a miscarriage, and had a D&C. The emotions you described are extremely familiar…it will be 4 years in January for me, but the memory is oddly fresh. Thank you for sharing…there’s a great deal of healing and hope when we share with one another.

I don’t know if these memories every really fade. It feels more like the angle has changed over the years and I can look back at the hurting, confused girl I was and I have so much compassion for her. I understand a small bit of God’s heartbreak and how well acquainted Jesus is with pain, even suffering the cross. It’s been almost 14 years for us. Yes, there is so much to be found in the me too’s. We were never meant to go it alone in this life. Thank you for sharing some of your experience with me. We’re never as alone as we often feel in the midst of it.

How true is this? “I wish I had understood that God is undaunted by my humanity.”

What an awesome great God we serve.

Thank you for opening your heart to us.

Thanks for reading Janene.

This is beautiful. Thank you for your words today!

Thanks for joining me here today.

Alia, As usual you bring beauty to the hard and hope to the hurting with your words. This sticks in my heart today, “I wish I had understood that answers are not the reason we ask the questions. Sometimes we ask the questions to say, Who are You really, God? Who are You to me right now in this pain? The questions are the place to admit our need, not just for answers, but for awareness of who God is.” Thank you!

Thank you Chara. Yes, those pesky questions aren’t so bad after all if we think of it as a dialogue between us and God. When we consider that God wants us to know He is who He claims to be and that might take some questions.

Jesus is indeed “the God of lost things” Praying for His special comfort…

Alia,

When my sister and brother-in-law lost their 5 1/2 month old daughter to trisomy 18, a friend shared with my brother-in-law that Jesus himself asked why on the cross: “Why have you forsaken me.” In fact He yelled it at God.

I never thought much past this encouraging idea. But the fact that asking God tough questions invites Him into our sorrow where He can reclaim the empty places is so beautiful.

Thank you for sharing from the rawness of your heart. A very important message for all.

I have dear friends who lost their daughter from trisomy 18 a few hours after she delivered and it was this asking of God to show up and these hard questions that ended up establishing one of the strongest faiths I’ve seen up close. The questions were the invitation for God to make Himself known in new ways. And amen to that insight of Jesus on the cross! I am in the process of writing a book and this very concept is a part of it. How do we approach a holy and just God with our questions and our doubts? How do we say God is good while still acknowledging the toll this broken world has on our souls? How can we be honest with God in our places of sorrow and anguish and yet like the Psalmist, turn around and praise God’s character.

(((♥))) No words, just a lot of love.

Thank you dear one.

I can’t offer much to add to this, I have seen women both from miscarriage and abuse want to pick up and go to Florida, not my idea of grieving, a vacation. I suppose people do grieve differently. I would be the heartbroken one, I have been for many reasons. I have a friend who lost a baby boy close to Chrsitmas, seasons and dates make things hard. Just be comforted by the fact that Jesus knows. I do know of a ministry couple who lost a daughter,

many years later they had another one, in a dream or vision, there had been two but something was wrong with one. God chose to let that baby come to Him. It gets into deep study, soul searching, how much we believe in healing. Why this or that? It is not for us to question a just God, it’s enough to know He heals our broken hearts.

We all deal with grief in different ways. If I wrote the next chapter after this it would contain so much denial and moving on at a pace that never allowed me any tears beyond that first day or two. Still I actually think there is a place to question a just God. I don’t think we’d have most of the Psalms if we didn’t. We certainly wouldn’t have much of Job. But hopefully our questions don’t terminate in accusation. Instead those questions allow us to seek and move into the character and nature of God as seen in the scriptures as we begin to see the Holy Spirit minister to us. We can come to a place that says with confidence, “Though he slay me, I will hope in him; yet I will argue my ways to his face.”- Job 13:15 I think God can bring us to a place where we have knowledge and trust that He heals our broken hearts but I think that faith most often starts with questions.

Alia, thank you for this post. Your loss has not been my experience but I’ve held the phone while a good friend cried about delivering her lifeless child. Currently, I have a family member who was given the news that her very wanted baby girl, may not survive the pregnancy. So often, as the friend/family member to the suffering, we wish we could make the pain and questions understandable and bearable. Your post is encouraging for the friend of the hurting to simply “be there” in the grief, just be there. Thank you for sharing.

Oh so much sorrow and devastating loss. Jesus be near. You’re a good friend, LaToya. Being there is often the best offering we have. You can’t rush it with trite answers. It’s like slapping a band aid on someone hemorrhaging from a severed limb. Sometimes we don’t get the answers we seek in the way we think we should but God is never silent in the face of pain. He is always speaking life back into barren places. He is always near to the broken hearted. Sometimes “helpful” people drown out the very voice of God by rushing the process instead of letting Jesus come near in the face of devastation. Letting Jesus bandage our wounds.

I’m so sorry for your loss. Two years ago on this date my young husband passed away leaving me with no family and no children.

Unimaginable sorrow and loss. I’m so very sorry for all you’ve been through and continue to go through I’m sure. I have no other words and don’t want to sound trite trying to come up with some. But thank you for your heart to comfort me when you’ve been through so much yourself. You are a blessing, Therese with the kind and generous heart.

Ohhhh, what a story! I felt it with you the whole way through. You write with such heart and courage. We lost a full-term baby boy (anencephaly). Actually, he would have been 27 today.

You write real and raw and with hope.

Thank you.

Wow! I am so sorry for your loss. It’s hard at every stage in different ways. We grieve so many lost things, yes? But I have had friends who’ve lost at term or just beyond and I grieve for that agony. I imagine you have quite a story as well. Twenty-seven years doesn’t necessarily lessen who’s missing but it gives you so much perspective. There is reality and there is hope. We are people who have to deal with both. The here and not yet of Kingdom Come, when things are as they should be and no one will feel the sting of death.

Beautiful response. thank you. xo

I love that. The naming of God’s character and identity is so foundational in how we deal with the struggles of this world. Knowing and then recalling the character of God is what faith looks like and it begins with our questions. Where are you? Who are you? Who do you say that I am? Faith is all one long dialogue where we come to know and believe that He is who He says He is and we can trust that.

I’m wondering if the asking of hard questions functions in the same way as the spiritual disciplines: they hold a place open in our hearts for God to work.

Yes! I think there is so much to this. The asking of questions and even the need for them. That empty space where we are confused and unsure and we need to know that we know. We need to stick our finger in Jesus’s wound and see that He understands. That it’s really Him there meeting us. We need a robust theology that can stand up to the questions of suffering and pain in the world, indeed in us. But so often we think that is the thing that saves us and we worry if we ask questions it means we’re off track or not having enough faith. The Psalms have ministered to me in this area. David came with so much torment and questions and longing. There was nothing but lack, empty space for God to come near. Sometimes that white knuckled grip on truth leaves no room for mystery or questions. I think it does a disservice to spiritual growth to never bring those questions to the Lord so that we can know that we know.

Alia Joy,

Sorry so late…I am so sorry for your loss. I pray God’s arms of comfort to surround you as I’m sure you continue, and will continue to grieve. I know, as a Christian, I feel like I’m not supposed to doubt, or be angry with God. If I am I’m not trusting. I so needed this reminder that He is mindful of our humanity and even in our questioning, He can invite us into a closer walk with Him. He gave me these emotions and therefore, I must believe He can handle them when they erupt. Thank you for giving me permission to be real and know that God loves me in it all.

Blessings and hugs to you,

Bev xx

Oh. my. This. Just this. My husband was diagnosed with AML in September of 2014. Since then we have endured months being separated from our children, only having weekend visits, during his treatment, which included two stem cell transplants. He is now 9 months post transplant and in remission, but, we know that the future is still very uncertain.

I, too, never wanted to ask “why?”. I think I am still afraid to do so. I am so afraid that the “me” I have pieced together will come shattering apart if I find that the faith I have clung so fiercely to, is shaken. I still too fragile. I am trying to strengthen my faith, but I can’t do that and have reserves left to strengthen myself too… Although I have found that there is a correlation between strengthened faith and a strengthened self. Funny how that works. Just when I think I can’t do this any longer, and I cry out to God, I find that somehow, I have managed to pull through for my family once again…

Powerful Alia. Thank you for being a voice for those who experience deep emotions and seek to love God through really challenging times. Such valuable words and a valuable testimony for sure. Love you.

Alia,

So sorry for the loss. Losses are hard and grieve us all. Thank you for sharing your wisdom here. God is the God of all-good and bad. Grieving is good and cathartic. Let your tears flow. “Questions are the invitation for Jesus to come to us in our sorrow and reclaim the empty spaces.” Yes and amen! It is ok to get angry and ask God why. Lean into Him and let His love flow into you! He will help you through all trials!

Blessings 🙂

You found all of us with your words, here. Thank you. We needed them. xo

God is undaunted by our humanity – yes. I have sat in church with so much pain, feeling like I was not handling it like I should, like other’s around me. But as I cried our to Jesus, He met me right where I was. It took me a while to get to the place where I could let go and reach up. Thank you for sharing your heart and blessing us. (Prayers for MaryGW below as you walk this road of grieving.)

This is powerful. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for always giving us the gift of new eyes to see Jesus in ways and places we didn’t expect. So grateful for you, friend.